Replacing Bibles with Tablets

Sign up

Sign up for the Worlds of Education newsletter.

Sign up

Sign up for the Worlds of Education newsletter.

Thank you for subscribing

Something went wrong

By Graham Brown-Martin

Is any education better than none?

It’s a vexing question but one that I believe we need to consider in light of well intentioned initiatives such as SDG 4 which, since launch in 2015, has rapidly become the target of commercial enterprises spotting a market opportunity.

The objective of SDG 4 is to “ ensure inclusive and equitable quality education and promote lifelong learning opportunities for all” as part of the Agenda 2030 for Sustainable Development. There is nothing in this objective that precludes free market model reforms and for-profit enterprises participating.

UNESCO’s position is clear: education is first and foremost a public responsibility that requires increased public domestic investment and increased bilateral and multilateral support, especially for sub-Saharan Africa. UNESCO encourages public-private partnerships to realise the right to education, but these must be based on equity, inclusion and national ownership, benefit the most vulnerable and operate within the framework of state-regulated standards and norms.

One of the commercial players taking advantage of SDG 4 is Bridge International Academies (Bridge), a US for-profit edu-business operating in Kenya, Uganda, Nigeria, Liberia and India but not without controversy in all territories.

Governments in both Kenya and Uganda have issued notices to Bridge to halt their expansion plans. The Liberian government has encountered global derision for its plan to outsource its entire education system to Bridge before reigning in their ambition. The UK’s Department for International Development (DFID) has come under criticism for using British tax payers money to invest in Bridge in Nigeria. Whilst in India their plan to open 4,000 low-fee schools subsidised by the commercialisation of private student data was discovered when their investment prospectus was anonymously leaked.

Regardless of these obstacles Bridge, who have received circa USD $100 million worth of investment from the World Bank, Pearson and Omidyar Network along with venture philanthropists Mark Zuckerberg and Bill Gates, plan to scale to 10 million children over 10 years.

Bridge has a significant investment in public relations and media control. Their first hire in Liberia wasn’t a teacher or local education specialist but, government lobbyist and former politician, Benjamin Sanvee as their Director of Corporate Affairs and Public Sector for Liberia. When I interviewed BIA’s co-founder chief development officer and chief strategy officer, Shannon May, she was joined on the call by not one but two PR handlers.

To listen to Shannon’s story and to read the promotional material distributed by Bridge one would readily believe that Bridge is on a humanitarian mission to provide access to high quality education to some of the poorest and most vulnerable communities. This illusion is shattered when one scratches beneath, what can only be described as, the thick veneer of marketing hyperbole that creates a reality distortion field around the organisation.

A recently published report from the UK’s International Development Committee, a watch dog for DFID, criticised Bridge suggesting that their claim of providing access to education for USD $6 a month was false despite being stated by Bridge in written evidence. Dr Joanna Härmä, Visiting Research Fellow at the Centre for International Education, University of Sussex, reported to the committee that, “ they claim that they educate children for about $6 a month. I presume they mean only their fee, because research has found that they charge around $15 a month in reality.”

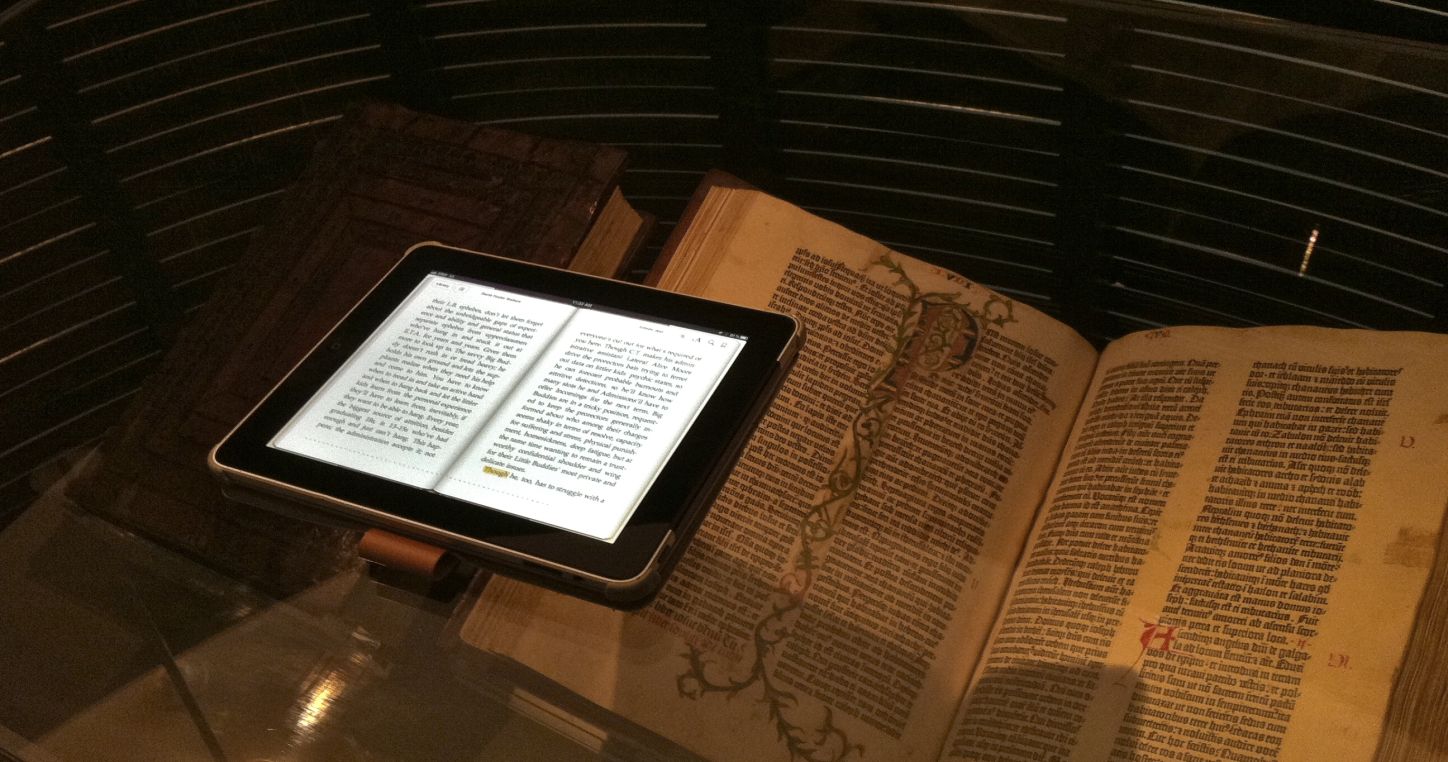

Providing access to high quality education for $6 a month is ambitious and Bridge seek to achieve this by radically reducing the teaching and school building costs whilst standardising as much as possible. They employ unqualified, non-union, teachers whom they provide a 5 week training course so that they can deliver pre-scripted lessons designed in the US from a low cost tablet computer. The “teacher” also uses the tablet to record student performance and other data which is sent back to Bridge in the US.

This narrow and industrialised version of education is focused on improving test scores in EGRA and EGMA assessment models but despite being in operation since 2008 the efficacy of Bridge’s approach is unproven. When asked for proof of efficacy Bridge direct you to their own promotional white papers and the reports by Stanford, Harvard & Brookings Institution that simply parrot from these papers without any further research . On closer inspection of Bridge’s data it is apparent that it “ has such considerable weaknesses that its claims need to be treated with scepticism”. These were the words of renowned statistician Prof Harvey Goldstein, University of Bristol, who took the trouble to actually study the data and methodology.

But it was the leaked investment prospectus from Bridge that was most enlightening. The document showed that Bridge and their shareholders have identified poverty as a market opportunity; the USD $64 billion “parent paid market” made up of the 800 million nursery and primary aged children living on less that $2 a day, and the $179 billion “publicly-funded charter school movement for low-income countries”.

The document shows how Bridge plans to subsidise its low fee education provision by monetising the data gathered from school children through their education career starting at nursery school. Highlights include:

“Usage of existing data for credit scoring and brokering to financial loan and other products”

“Creation and brokering of low-cost health insurance”

“Uniform Sales — will grow to 15% of revenue” (in addition to the monthly school fee)

“Lunch Program — potential for 10% revenue share” — Bridge take 10% of the children’s lunch money

Suddenly an affordable learning programme looks far more expensive, socially and financially, than the label price. Seen through the prism of “big data” this is looking less like an education play and more like a surveillance play of Edward Snowden proportions. In this light, the investments in a commercial organisation by the likes of the US and UK governments as well as Facebook via Mark Zuckerberg begins to make more sense than simply philanthropic “development”.

So returning to my original question, is any education better than none?

No one can deny that lack of access to education for so many of the worlds citizens is a crisis but is this a reason to ask them to give up their civil liberties in exchange for it?

http://grahambrownmartin.com

The opinions expressed in this blog are those of the author and do not necessarily reflect any official policies or positions of Education International.