‘May’ Days in March: Bridge Asked to Account by UK Parliament

Sign up

Sign up for the Worlds of Education newsletter.

Sign up

Sign up for the Worlds of Education newsletter.

Thank you for subscribing

Something went wrong

By Susan L. Robertson, University of Cambridge

It is not often a US-based private education contractor for the delivery of services gets asked to appear as a witness to give evidence to a UK Government International Development Committee hearing in the House of Commons, London.

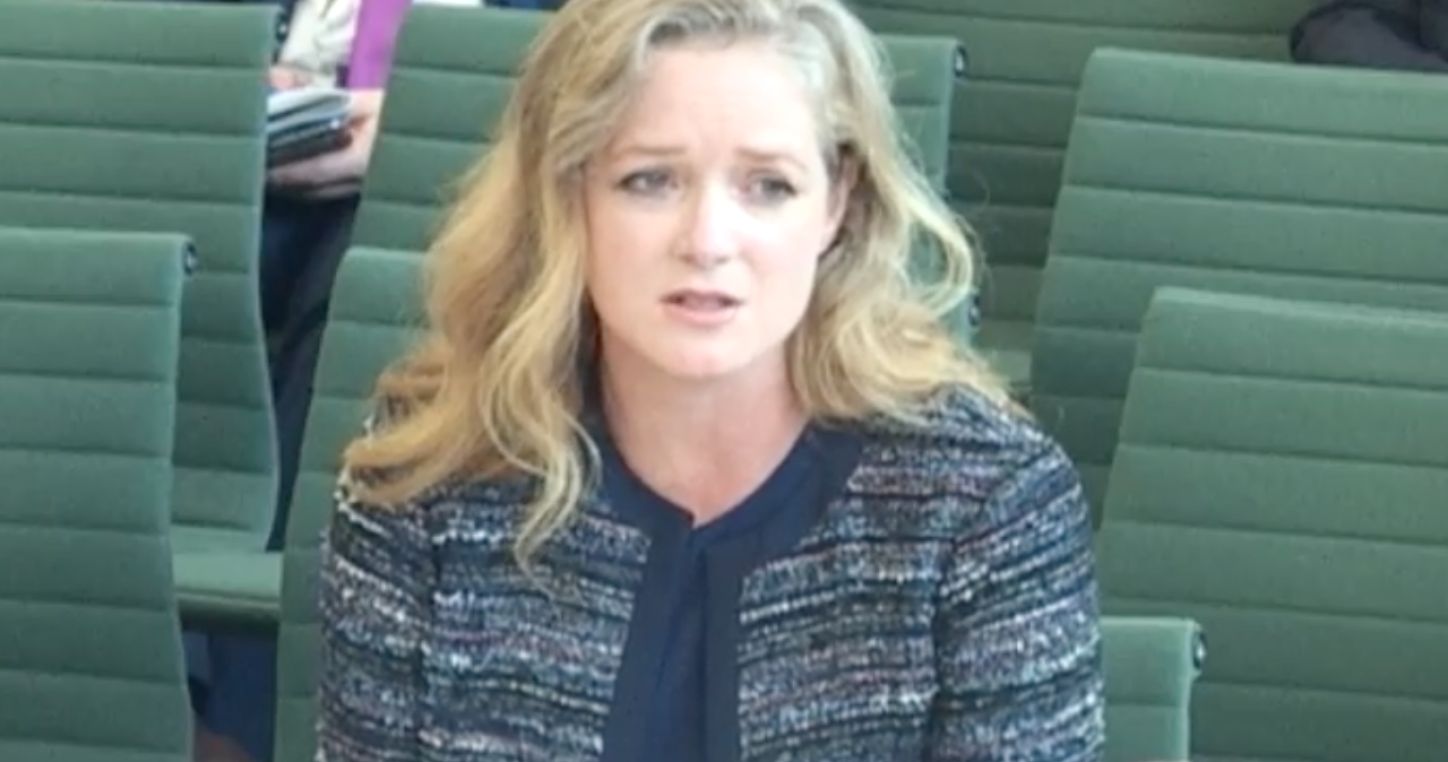

But just one week ago, on Tuesday 28th March, 2017, co-founder of Bridge International Academies, Dr. Shannon May, faced a barrage of questions from the Committee members on the activities of Bridge, and the nature of its relationship to the UK’s aid agency, the Department for International Development (DfID).

The Committee Chair, Stephen Twigg began with his first question for May: “According to your website, Bridge’s investors are mainly venture capital firms, philanthropists and development finance institutions. My understanding is that to date DfID is the only donor agency to have invested directly in Bridge. Is that correct?”

The answer from May took some time to emerge: “We have been working under a contract with DfID specifically in Lagos State to improve our learning outcomes for marginalised children”. For DfID, this relationship with Bridge is particularly controversial. This is UK aid money going directly into a profit-making venture by Bridge and its venture capital backers.

Yet with the count-down to the delivery of Brexit less than 24 hours away, DfID’s relationship to this for-profit company did not get the public airing in the press that it deserved. For the following day was no ordinary day either. Rather, another May – in this case UK Prime Minister, Theresa May, was to deliver a fateful message to its European cousins; a letter triggering the exit of the UK from the European Union.

Buoyed by bravado and not fact, ambition and not measured evidence, Mrs May’s account of the future for the UK was a heady mix of massaged meanings into post-facts and post-truth. This was a day that veered between the multiple meanings of ‘may day’ – from a signal of distress to rowdy celebration.

So how did the other Dr. May fare on this mad March day? An analysis of the video and transcript of the hearing is revealing. What were the facts of this relationship between Bridge and DfID? And why should we care? The fact of the matter is that Bridge International Academies has not only caught the attention of the global educational community with its breath-taking ambition - to roll out a for-profit model of education to reach more than 10 million children across a dozen countries, but it has been mired in controversy over its model of development and operations.

Who, then, are Bridge International Academies? Briefly it is a US-headquartered international education chain founded in 2007 by Shannon May and Jay Kimmelman. It has the backing of venture capitalists, such as Facebook’s Zuckerberg, the World Bank’s International Finance Corporation who lend to the private sector, and corporate philanthropists like Gates. It promotes itself as a ‘low-cost’ fee-based, network of for-profit primary schools aimed at families living in low-income countries on US$1.25 per capital per day.

Its rapid expansion since 2009 has been remarkable. The company has set a target of 3,337 schools by 2018, enrolling close to 2.5 million students. Bridge operated in Uganda (until its schools were closed in August 2016 for failing to meet government standards). It continues to operate in Nigeria, and has according to Action Aid’s David Archer, a lucrative $US8 million contract to operate publicly-funded private schools in Liberia (with Bridge one of 8 providers in the initiative called Partnership Schools for Liberia) which began September 2016. Yet as Archer points out, if the total budget for Liberia’s education is around $41 million to service 3,000 schools, and Bridge gets around 1/5 of this to run 24 schools, the thorny matter of profiting from already cash-strapped governments aside, the question of what’s left for the rest over the long term is a particularly relevant one.

Why do we care? Well at its simplest, this seems to be a case of Liberia seeking to outsource education, and in doing so, outsourcing its responsibilities as a government to educate the next generation.

But there is more. Bridge deploys a unique business model: economies of scale, and the use of new technologies. The parallels here with the rise of Taylorism just over a century ago cannot be overlooked, where the complex tasks of workers were driven by the logic of efficiency, with workers (in this case teachers) losing control over the nature of their work. And whilst this model is represented as an education innovation by Dr May in her account to the Committee, (which it surely is), it is not the case that all innovations are by definition socially desirable. Indeed Taylor – in his presentation in 1912 to the US House of Representatives - was to describe his principles of scientific management the new ‘alchemy’; a technique able to convert the management of work into bigger profits.

In her description of Bridge to the International Development Committee, Dr. May described Bridge as a ‘mission-driven social enterprise’. Quizzed by Committee member, Pauline Latham, around this unusual use of the term ‘social enterprise’, Latham pointed out that we normally view a social enterprise as a not-for-profit organization. Dr. May responded: “Perhaps it could be just a difference in interpretation of terms”. Earlier on in the hearing, Dr. May described a social enterprise as meaning: “we have been structured to ensure that we are able to serve families at a fairly minimal fee level. These are families that are earning $1.25 per day per capita”.

This response echoes of massaged meanings, post-fact and post-truth. Perhaps we might say that rather than Bridge being a social enterprise, it is Bridge’s owners who have been particularly socially-enterprising, recognizing an opportunity to make a profit from the very poor with the promise of an education to radically transform their future. Alchemy indeed. Taylor would be cheering from the side-lines, but his disenfranchised workers would not.

And then there is the question of evidence. Does it work? Is a tablet driven learning environment effective? What is the role of the teacher in this learning relationship? In her evidence to the International Development Committee, Dr. May described a tablet driven education as interactive. Again this is a strange twist in the meaning of interactive. Typically we mean the teacher interacts with the students, and not Headquarters. Which leads us to conclude that the teacher is just a cypher for learning and managing decisions made in the head office of a distant country thousands of miles away.

But let’s return to the issue of evidence. In Dr. May’s words, Bridge is “scientifically-driven and evidence-based”. In her evidence to the Committee, she pointed to Liberia, stating that a small evaluation study has shown that in comparing 6 publicly-funded Liberian schools working with Bridge, with 6 schools not working with Bridge, Bridge were able to generate “radical” learning gains after just 15 weeks. Alchemy again! Without wanting to be too cynical about things, perhaps we ought to be aware of the basis on which claims to science and rigor are made. Are each of the schools the same? Do they receive the same funds? Are the class sizes the same? Is the effect size of simply being in an innovation being discounted or included? World experts on assessments and statistics, like the University of Bristol’s Professor Harvey Goldstein, have questioned Bridge’s loose understanding of evidence and rigour in their Kenya Report to learning gains.

The spectre of post-truth and post-facts also casts its dark shadow even further. Asked by the Chair of the Committee about “allegations of the Bridge staff exhibiting threatening behavior toward independent researchers” in Uganda, May’s response was: “…this gentleman…was misrepresenting his identity stating he was someone who worked for Bridge. Parents and teachers recognized he did not work for Bridge. They called in to our Bridge customer service line, and in some cases called their local police station, which many parents in the UK would also do if there was a stranger who was impersonating an employee of the school”.

The ‘gentleman’ here is Curtis Riep, a Canadian independent researcher examining Bridge’s operations in Uganda. Riep was cleared by the police of all charges and especially accusations of him misrepresenting his identity. What has Bridge to hide, or lose, with this kind of threatening behavior? Lots of course, including the promise of profits into the future. Losing its right to operate in Uganda because of sub-standard provision, with questions about its operations in Kenya still to be resolved, its relationship with DfID being scrutinized, there is a lot at stake. Which is why its recent contract in Liberia is both important to them, for losing this, and its investors, who are likely to get edgy.

Profit and education is a bad mix. It is not the new alchemy, nor the magic money making machine that will deliver to the poor whilst exploiting the poor. How can it. The sums don’t add up. Well, not really, unless we are all seduced by post-truth and post-fact. Which is why close scrutiny, and hard questions in search of hard answers, are all the more important, especially when education is increasingly seen by the 21st Century entrepeneurs and investors as ripe for easy profits.

The opinions expressed in this blog are those of the author and do not necessarily reflect any official policies or positions of Education International.