Education International analysis of the European Credit Transfer System for Vocational Education and Training (ECVET)

Localism of European Vocational Education and Training

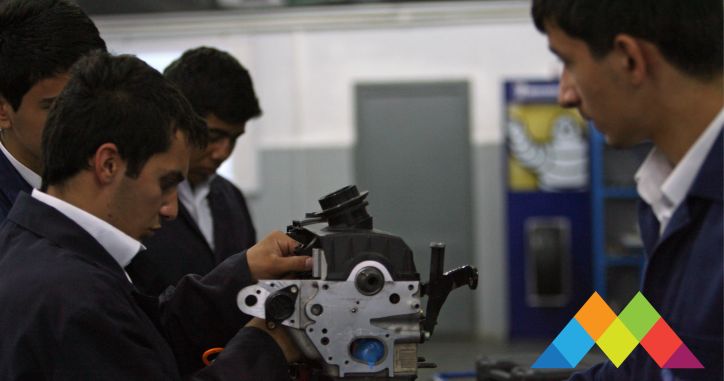

Students in vocational education and training (VET) have traditionally not had many opportunities to study in foreign institutions throughout Europe, as opposed to their friends in higher education. As their education and training has a very local profile, it has often implicitly been assumed that a mobility experience would not have many added benefits. Only around fifty-thousand students participate in EU-mobility programmes for VET each year. However, the VET-sector has convinced the European Union that more opportunities are needed. An international dimension for VET will greatly enhance quality, similarly to the benefits of Europeanisation of the higher education sector, through the Bologna Process. The European Commission has therefore proposed a recommendation for a European credit system for the VET sector (ECVET) for adoption by the European Parliament and Council in April 2008. Education International is committed to a greater internationalisation of the VET sector and a greater mobility of students. It is however highly sceptical that the current proposal will facilitate this goal. The Bologna Process, of which Education International is a consultative member, has greatly helped the implementation of the European Credit Transfer and Accumulation System (ECTS) for higher education. EI finds it surprising that the ECVET-proposal fundamentally ignores the lessons that the higher education sector has drawn from its experience. By developing different systems for different education sectors, the European Commission risks to break down fragile links between VET and higher education. A European credit system for VET is highly needed, but EI maintains that the current proposal is not good enough. While the explicit aim of the proposal is ‘to facilitate transfer, recognition and accumulation of learning outcomes of individuals who are aiming to achieve a qualification’, it might achieve the contrary. What is ECVET? ECVET divides a curriculum into small units of study or other activity (such as internships) with defined learning outcomes. These units can be considered as the building blocks of a study-programme and can for example be small courses or internships. Units themselves will be divided into credit points, which will typically add up to a total of 60 credits per full-time study year. These credits are calculated on the basis of learning outcomes. Different learning outcomes can get different amounts of credits, based on the challenge for the learner. If a student will study or take an internship abroad, the institution at home will make an agreement with the institution abroad in which the different units and learning outcomes that will be dealt with are being described. This so-called learning agreement will be signed between the two institutions and the student, so that the experience will be recognised in the curriculum at home as soon as it is completed. The second aspect of the ECVET system is thus that VET-institutions will form international networks in order to facilitate mobility. According to the proposal for a recommendation, the EU-member states should implement this system in all their VET-institutions by 2012. Thus, the Commission envisages that by 2012, all VET curricula in Europe could be described according to the ECVET system. ECVET differs from the ECTS system and it is hard to predict if the two systems will be compatible. The ECTS system is based upon a calculation of notional student workload and learning outcomes. To define the credits, a higher education institution first defines a framework for a curriculum, by developing learning outcomes at different stages (for example for individual courses). The institution then calculates the average workload that a student needs to complete a unit. With this calculation, the institution can plan a curriculum in such a way that is neither too heavy, nor too light. Central in this process is communication between curriculum designers, teachers and students, who jointly plan and evaluate the credit system. The credits are then published and can be used for progression within or transfer between different higher education institutions. Typically, a full time year of studying in higher education consists of 60 credits. A Bachelor programme will typically consists of 180-240 credits, while a Master programme would typically consist of 60-120 credits. Why is ECVET not up to the task? Describing learning outcomes as a basis for credits is a highly complex task. It is therefore doubtful that the same methodology to describe learning outcomes will be used throughout Europe. The proposed method allows for a very broad interpretation of units or learning outcomes and does not provide a clear procedure to describe or evaluate them. The only reference point for the system is provided by the European Qualifications Framework, which describes general outcomes of qualifications at all levels of education. It is therefore nearly impossible to predict that learning outcomes will be described in a common way among all VET-institutions around Europe. Trust, which is fundamental to recognition, will therefore not necessarily be increased, but could even be decreased with the current proposal. The fundamental aspect of the ECTS system, student workload as a way of calculating credits, has completely been rejected in the ECVET system. As an average workload provides a quantitative tool to calculate credits, it was instrumental to the success of the ECTS system. The 60 credits for a full time year of studying in higher education have a quantitative basis in the reality of students’ workload. Moreover, students’ workload is an important determinant of the quality of education. Only by measuring effort versus outcomes, is it possible to know if the student learns something new and challenging. The typical argument for rejecting the notion of workload for the VET system is that systems are too diverse to allow for such a broad indicator. However, such an argument is strange considering the much higher diversity of the higher education system. Whereas VET institutions in Europe are typically highly subject to government regulation (excluding VET provided on a commercial basis), higher education institutions themselves are autonomous and provide very different courses and programmes. Yet it has been possible, over a period of nearly 20 years to develop this common credit system in higher education in 46 countries. In VET, such a task would naturally be challenging, though it is highly likely to be easier than in higher education. The differences between the ECTS and ECVET system prevent further cooperation between higher education and VET. As the European University Association notes in its feedback on the system ‘By developing two different systems of credit accumulation for VET and higher education, artificial barriers are being constructed, that will complicate mobility between the sectors at a time when the increasingly widespread use of ECTS has been facilitating such movement. The distinctions between those two sectors are often blurred, programmes that are part of VET in one country are part of higher education in other countries (e.g. kindergarten teacher, nursing) and thus already use ECTS (EUA 2007).’ EI further fears that it might become harder for a student from VET who wants to proceed into higher education. As many groups from lower socio-economic backgrounds study in the VET-sector, the ECVET system will not only harm mutual recognition but also social mobility. Concerns of students, teachers and institutions have barely been taken seriously in the process towards establishing the ECVET system. The European Commission organised an online consultation process between November 2006 and March 2007 in which it asked all relevant institutions to contribute to the discussion with their views. Within the consultation process, doubts have been expressed from nearly all contributors, but the proposal has not been significantly altered accordingly. Moreover, the period of consultation has been very short. The European Trade Union Committee for Education notes in its contribution that ‘In a number of Member States, proper consultation of stakeholders were not organised by the ministries (ETUCE 2007).’ The higher education sector feels that the proposal has been pushed through because of political ambitions of the European Commission, as can be seen from the amount of negative responses from the sector in the consultation process. This sets a dangerous precedent for the implementation of the system. Implementing a credit system requires commitment from all key stakeholders to describe and evaluate the credits according to reality. Currently, this commitment does not exist, providing a final flaw of ECVET. Developing a credit system for lifelong learning Education plays an important role in increasing opportunities for children, young people and adults alike. Different levels and sectors of education should be better linked in order to increase opportunities for all. Modern education policies therefore need a ‘lifelong learning’ approach. Education International believes, together with the European Trade Union Confederation (ETUC 2007), that a credit system for lifelong learning would be beneficial to these goals. The purpose of such a system would not be limited to international comparability and recognition of learning experiences. Indeed, it would be very useful in a national context as well, as learners often get stuck along the way, without possibilities to continue in another education track. Such a credit system should be based on principles of workload, learning outcomes and accumulation. This set of principles has a proven record in higher education and will lead to a more transparent and recognised education. What will happen now? The proposal of the European Commission will have to be adopted by both the European Council and the European Parliament in the coming months if it is to become a reality. However, as the proposal has been prepared in cooperation with the member states, it is not likely to be fundamentally altered during this procedure. Moreover, the rapporteur of the European Parliament, Dumitru Oprea, has published a draft report in July 2008 and supports the proposal from the Commission. The main amendment it proposes is to delay the implementation time by 5 years in order for it to be successful. It is therefore likely that the recommendation will soon be adopted by the European Union. The member states then start to - voluntarily - implement the recommendation. As the text is not legally binding, the Commission will plan to implement the recommendation through the Open Method of Coordination. The member states can alter the text in its implementation or decide not implement it at all. To prevent this, the Commission will develop a number of tools to encourage a practical mind towards implementation, coupled with peer pressure towards the member states. Firstly, the proposal will be implemented in a number of test cases, for which the European Commission provides financial support. Also, a users' guide, similar to the ECTS User’s Guide will be developed, which should further help the implementation process. Finally, the Commission will regularly take stock of the implementation process. In case member states fail to implement the recommendation, it will remind the member states of their commitments. Within Europe, EI and the European Trade Union Committee for Education (ETUCE) continue to monitor and respond to developments that are part of the Bruges-Copenhagen Process. These include the proposals by the European Commission for a credit system for VET, but also proposals such as a quality assurance system for VET and the already adopted European Qualifications Framework.