Using the best tools for development cooperation work

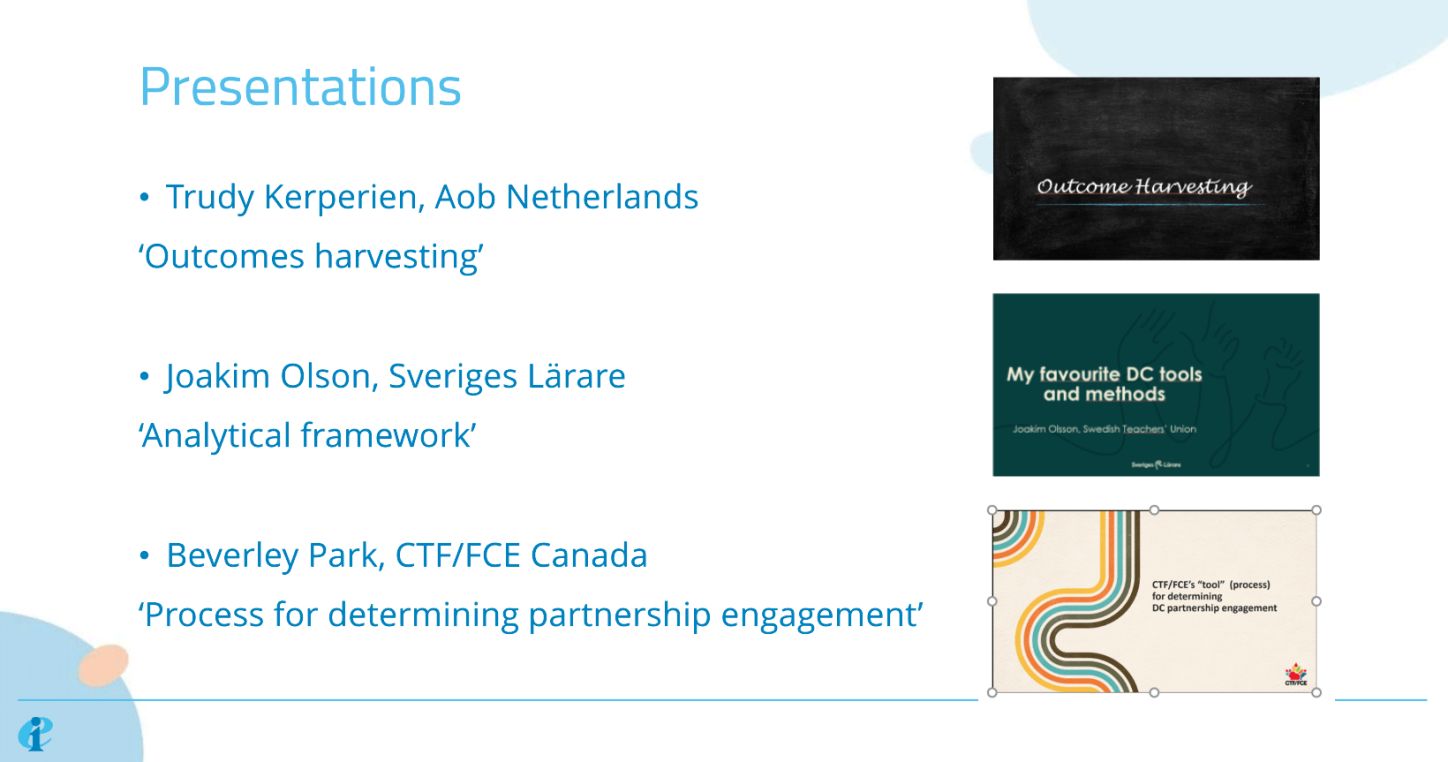

Education unions that promote and fund solidarity projects evaluated and discussed their favourite development cooperation (DC) tools and how they help deliver the best results for their partners.

The capacity building and solidarity unit at Education International organised a DC Café on September 25th to discuss development cooperation tools with project funding organisations.

Participants agreed that when planning and carrying out solidarity projects, they use methodologies that they adapt to the context, to the organisations taking part, to the requirement of back donors, etc. These methodologies, tools and strategies all have distinct features and can be adapted to what unions need and want to focus on. They therefore have undeniable implications on what the project will look like and the engagement of the parties.

A founding principle: Partnership

While Beverley Park, Director of the International and Social Justice Programme at the Canadian Teachers’ Federation (CTF) , deplored that her union lost the Canadian government’s funding back in 2012, “which limits what we can do because we have very limited funding”, Park noted that this was “a blessing because we are not tied therefore to some of the requirements that the government might have around reporting.”

“What I want to share with you is not so much a tool but a process: how we determine with that very limited funding what we are going to support, where we are going to work,” she said. Her union focuses on three core areas, she said: teacher professional development; gender equality; and union capacity building.

She was also adamant that partnership means analysing the local context, the union needs, the union capacity and the union readiness to cooperate. Park went on to insist on “a gradual release of responsibility” between cooperating partners for sustainable projects.

Mixing various tools

Joakim Olsson of Sveriges Lärare from Sweden later presented various tools and methods for project planning and evaluation, including Zoom for quick follow-up and decision-making, annual evaluation and planning meetings, SWOT (Strengths, Weaknesses, Opportunities, and Threats) analysis, analytical frameworks and joint agreements.

It is important to look for long-term sustainability and enhance local ownership by asking for a steady increase in own funding, he underlined, adding that “it is the local partner organisation that formulates the proposal for project activities and budget”.

He also acknowledged that there is a “fine line between being engaged and meddling” and that cooperating partners should avoid sending “experts” that are unfamiliar with the local context.

Giving the concrete example of a DC project in Latin America, Olsson explained that a consortium had been created to support the EI Latin America office, with one single agreement grouping the six parties to the agreement, and an annual evaluation and planning meeting over three days (whether in situ or remotely).

Outcomes Harvesting

Trudy Kerperien of the Algemene Onderwijsbond/Netherlands also introduced the Outcomes Harvesting methodology, which is a participatory and interactive evaluation method that helps document and assess complex projects in a participative and inclusive way. It focuses on significant changes in social actors' behaviour resulting from an organisation's actions, rather than just measurable indicators.

For Kerperien, the method is mostly used to analyse the effectiveness of strategies that are difficult to measure, such as lobby and advocacy work.

“Through Outcomes Harvesting, we acknowledge that often we can’t attribute change directly to our interventions, but we want to explain how we have contributed to positive outcomes as a consequence of our actions,” she said.

She explained the methodology, which involves documenting and observing outcomes throughout a project period. It requires keeping a logbook as a living document and systematically working on a long list of items to keep notes of everything that happens.

For Kerperien, the Outcome Harvesting methodology is interesting, as it goes beyond the obvious results and easily measurable outputs and takes into account non-linear routes to results.

She was also appreciative of the fact that it looks at unplanned, unexpected and also negative outcomes, at your contribution instead of attribution (which is very difficult to assess), and at how your work changed the behaviour of people.

EI’s Director for the Africa Region, Dennis Sinyolo, agreed that “it is critically important for us to focus on outcomes, not outputs of a project – for example, what was done? How many people attended? – as is often the case for member organisations on the field.”

Focusing on outputs as it is current practice in most of education unions’ development cooperation work, “is problematic because unintended outcomes might as well be important, go far enough in telling us what change happened as a result of the project or intervention,” he said.

Sinyolo also supported the idea of bringing “engagement versus meddling. That's the hardest part. Quite often projects come predefined in terms of priority areas for member organisations to have their proposals approved, they need to fit into that predefined priority area of work. But sometimes, the local priorities can be different. The project needs to be anchored on the real problems affecting unions on the ground.”

EI’s Florian Lascroux further suggested to set up a database of DC tools where members can store different tools and documents that could be of use for other organisations. Participants approved the idea and agreed to inform other organisations about the database.

This DC café meeting may lead to future such meetings on specific tools based on attendees' interests.