"Repairing the infrastructure of public education amidst the breakdown", by Sam Sellar

Sign up

Sign up for the Worlds of Education newsletter.

Sign up

Sign up for the Worlds of Education newsletter.

Thank you for subscribing

Something went wrong

While trying to make sense of the crisis caused by COVID-19, two well-worn lines keep coming to mind. The first is attributed to Lenin, who apparently claimed, when describing the Russian Revolution, that ‘there are decades when nothing happens; and there are weeks when decades happens’.

The second is often attributed to Churchill, but almost certainly has a longer history: ‘never let a good crisis go to waste’. Both lines express the truth that real change is rare, and every crisis is an opportunity.In this blog post I reflect on one change occurring in education now—the intensification of datafication as commercial actors use the shuttering of schools to advance their interests—and how we might respond. Ben Williamson has provided insightful analyses of how ‘emergency edtech’ is using the crisis to create ‘pandemic markets’ and to embed their platforms as part of a ‘new normal’, rehearsing the now familiar promise that ‘education is broken, tech can fix it’ ( https://codeactsineducation.wordpress.com).

Many of us have come to rely upon new technologies to teach, learn and meet over the past few months and, in terms of the embedding and acceptance of these technologies, we may well have seen change that could otherwise take decades. In the process, more and more opportunities are created for the collection of data from us. We are being encouraged to accept the necessity of this surveillance, of tracking and tracing our activity, for our wellbeing and that of our families and communities.

Data is now the most coveted source of value for tech companies. Surveillance capitalism involves locking customers into platforms that enable what Shoshana Zuboff (2019) calls rendition: ‘the concrete operational practices through which dispossession is accomplished, as human experience is claimed as raw material for datafication and all that follows, from manufacturing to sales’ (p. 233).

As we use many of the digital interfaces that we encounter every day, our experience is rendered into data and we are forced to surrender, often unknowingly, to the logic of surveillance capitalism. Rendition destroys our privacy by privatizing our information. The present crisis should give us even more cause for concern about data privacy in education as companies accelerate the roll out of business models based on rendering as much data as possible from users.Zuboff suggests three ways that we can protect our privacy today: taming, hiding and indignation. We can seek to tame the power of tech companies through legal instruments such as the General Data Protection Regulation, or we can try to hide from their gaze by disconnecting from platforms and masking our identities and activities. However, large and powerful tech companies are not easily tamed and hiding implies acceptance of what we are hiding from. The pandemic is likely to further undermine both strategies by creating a state of exception in which we are encouraged to set aside concerns about data privacy in order to sustain ‘business as usual’ and protect ourselves and others.

This leaves us with indignation. An important condition for the emergence of indignation is recognition that the advances of surveillance capitalism are not inevitable. Dissatisfaction with the promises of big tech and the capture of our experience through datafication can be instructive, because it ‘teaches us how we do not want to live’ (Zuboff 2019, p. 524). The current crisis is a particularly propitious moment for such a lesson. The rapid extension of digital infrastructures for learning is occurring at the same time that many have felt the loss of physical spaces dedicated to education.

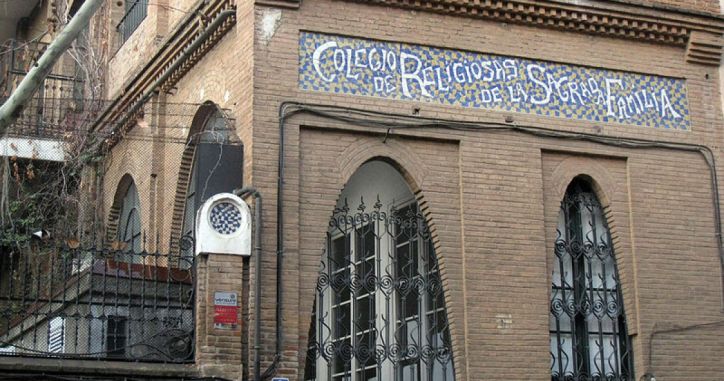

Schools are critical public things that provide a ‘world-stabilizing infrastructure’ for action in concert (Honig, 2017, p. 96). Schools serve as spaces in which we educate collectively, as opposed to the personalisation of learning that new education technologies promise. We generally only notice infrastructure when it breaks down, and the shuttering of schools has created a ‘glitch’ that has drawn attention to aspects of schooling that were previously taken for granted.

Every crisis is an opportunity, and almost always more than one. While the current crisis creates fertile conditions for growing privatization in schooling, and for the expansion of business models premised on extracting data from us, it can also teach us how we do not want to live. We have the opportunity now to highlight the problems of privatization in education amidst a structure of feeling that is more acutely attuned to the possibility of decades changing in weeks, to the transitory nature of what so recently felt solid. The crisis thus also creates fertile conditions for disrupting the sense that dispossession of educational experiences through datafication is inevitable, and for growing indignation at this erosion of public education.

The opinions expressed in this blog are those of the author and do not necessarily reflect any official policies or positions of Education International.