Education voices | How a union is mobilising communities against child labour in Burundi

Sign up

Sign up for the Worlds of Education newsletter.

Sign up

Sign up for the Worlds of Education newsletter.

Thank you for subscribing

Something went wrong

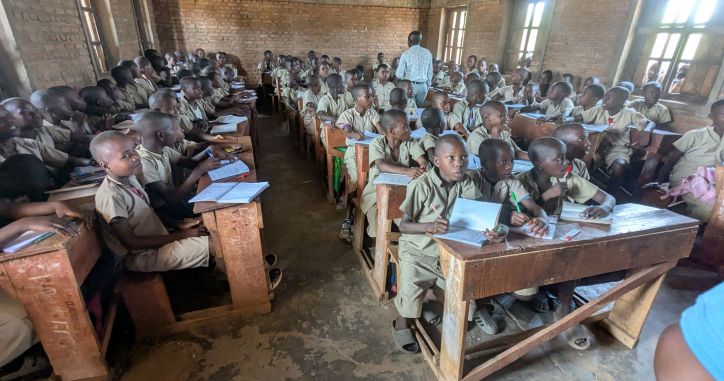

Since 2021, projects run by the STEB education workers’ union of Burundi have enabled more than 900 former child workers to return to school. Remy Nsengiyumva, President of the STEB, reflects on the strategies used in these projects supported by Education International, the AOb, NEA, GEW Fair Childhood Foundation, and Mondiaal FNV.

Worlds of Education: How would you describe the child labour situation in the community before the launch of your projects?

The field surveys we carried out in our three project areas (Rukaramu, Gihanga, and Ndava) revealed that one child in six was not attending school. In Gihanga, for example, 1,742 out of a total of 10,047 children were not in education.

The children in these three areas are generally used for work in rice-growing, brick-making, and livestock farming. More recently, our surveys have also revealed the use of children in petrol trading from border areas, due to the fuel shortages in Burundi.

The main causes we have identified are negligence on the part of parents, children’s behaviour, a lack of awareness, non-compliance with the law on free education, and in some cases poverty.

Worlds of Education: Do your projects change how teachers and school directors operate?

At the start of the project, the STEB’s first training and awareness-raising sessions are aimed at teachers and management staff. They typically cover children’s rights, the minimum working age, and the law on compulsory education. When the staff taking part learn more about children’s rights, they understand, for example, that employing children in their own homes is prohibited. Prior to our training, there were cases of teaching staff using children as helpers in their own homes. This stops being the case when our projects are launched.

The teaching staff trained through our projects also become aware of the importance of following up on children who are regularly absent from school: trying to understand the reasons for these absences, contacting the parents, taking swift action before the child drops out.

We encountered cases where the school management would demand money to re-enrol children who had dropped out of school. This practice has disappeared in our project areas, for fear of being reported but also because there is a growing awareness that all children of school age should be in class, not at work.

In the schools where our project is implemented, the STEB has teachers who act as “focal points”: they are our local relays who work in conjunction with the school directors to coordinate the school clubs to combat child labour. They also monitor former child workers who have returned to school, to minimise the risk of them dropping out again.

Worlds of Education: What is the role of the school clubs to combat child labour?

The clubs are made up of students under the guidance of a teacher. They play an important role in raising awareness, through activities such as street theatre performed in the community. During these short performances, the children play the role of negligent parents or badly-behaved children. They raise awareness among their peers and parents about the consequences of labour exploitation and the importance of education.

Worlds of Education: How do you involve the community in your projects?

It all starts with an initial contact meeting to which we invite all sections of the community: representatives of parents, churches and collines (a colline is a small administrative unit in Burundi). We then give these people training on the subject of child labour, so that they can help us raise awareness. These are the people who visit households to find out who is studying and who is not during our field surveys at the start of the project. By entrusting them with this task, we ensure that all households are checked or visited. These visits already provide them with an initial opportunity to raise parents’ awareness.

Some of them become members of the monitoring committees that we set up in each colline. These committees sometimes impose local penalties, such as fines, on recalcitrant parents. The parent is thus obliged to take the child back to school.

Worlds of Education: Can you tell us about a child who has returned to school thanks to one of your projects?

I can give the example of a nine-year-old girl from Rukaramu. She and her mother were abandoned by her father. Her mother told her that, to survive, she had to go to work in the fields with her instead of going to school. The girl was not able to go on to year two because of the situation. She would sometimes talk about it to other children of her age. One of the students who was a member of our clubs went to talk to the girl’s mother who responded that she was too poor to afford the school supplies. The mother of the child who was a member of the club offered to help her with the supplies. During the same period, the mother of the nine-year-old girl attended one of the club’s street theatre performances and was moved by the message. She immediately went to speak with the STEB General Secretary, Jocelyne Kabanyana, and the head of the colline, who ensured the follow-up needed to enable the girl’s re-enrolment in school. She is very hard working and will soon be starting year five.

Worlds of Education: Do your projects change the way the community perceives both education and child labour?

Yes. The parents and the community in general were not aware that child labour hinders children’s physical, mental, social, and psychological development. We have seen a change in mindset. Some people didn’t realise what they were doing by employing children, like the teachers who didn’t know the legal working age and didn’t really understand the consequences for children who don’t study.

Thanks to our awareness-raising campaigns, our outreach on the ground, and our street theatre, we’re now seeing that almost the whole community understands that a child’s place is in school and not at work. This is reflected in the large numbers of children returning to school, even from the poorest households.

Poverty is often cited as the main cause of child labour, but this is not necessarily the case. Children who drop out of school are just as likely to be from poor families as from wealthier ones. The main reasons for dropping out are negligence, or a total lack of awareness.

Worlds of Education: Does this kind of project to combat child labour also help your trade union in any way?

This project is very important for the STEB’s development in terms of our visibility among the teaching community, and even among administrative and government representatives. The community and the government think that unions are there to demand better working conditions for education workers, but we are also there to ensure quality education and education for all.

This project is also improving social dialogue on a broader scale: when trade unionists from the STEB enter a government office, they are now recognised for their activities in the fight against child labour. Trade unionists are therefore given a better welcome and are likely to feel more comfortable talking about what is going well, and what is not.

As for the union leadership, the project visits we make are also an opportunity for us to engage with and assist our members. These encounters within the framework of a project to combat child labour do not prevent us from talking about the trade union situation. Some teachers have joined the union after seeing what we are doing in their schools and communities to combat child labour.

The opinions expressed in this blog are those of the author and do not necessarily reflect any official policies or positions of Education International.