Trust cannot be automated: education unions shape the AI future

Around the world, artificial intelligence is being rapidly integrated into education systems. Governments and technology companies promise efficiency, “personalised learning” and data-driven decisions. But for teachers and their unions, AI raises far more fundamental questions: Who controls education? What happens to professional autonomy, democratic accountability, equity and labour rights when algorithms mediate teaching and learning?

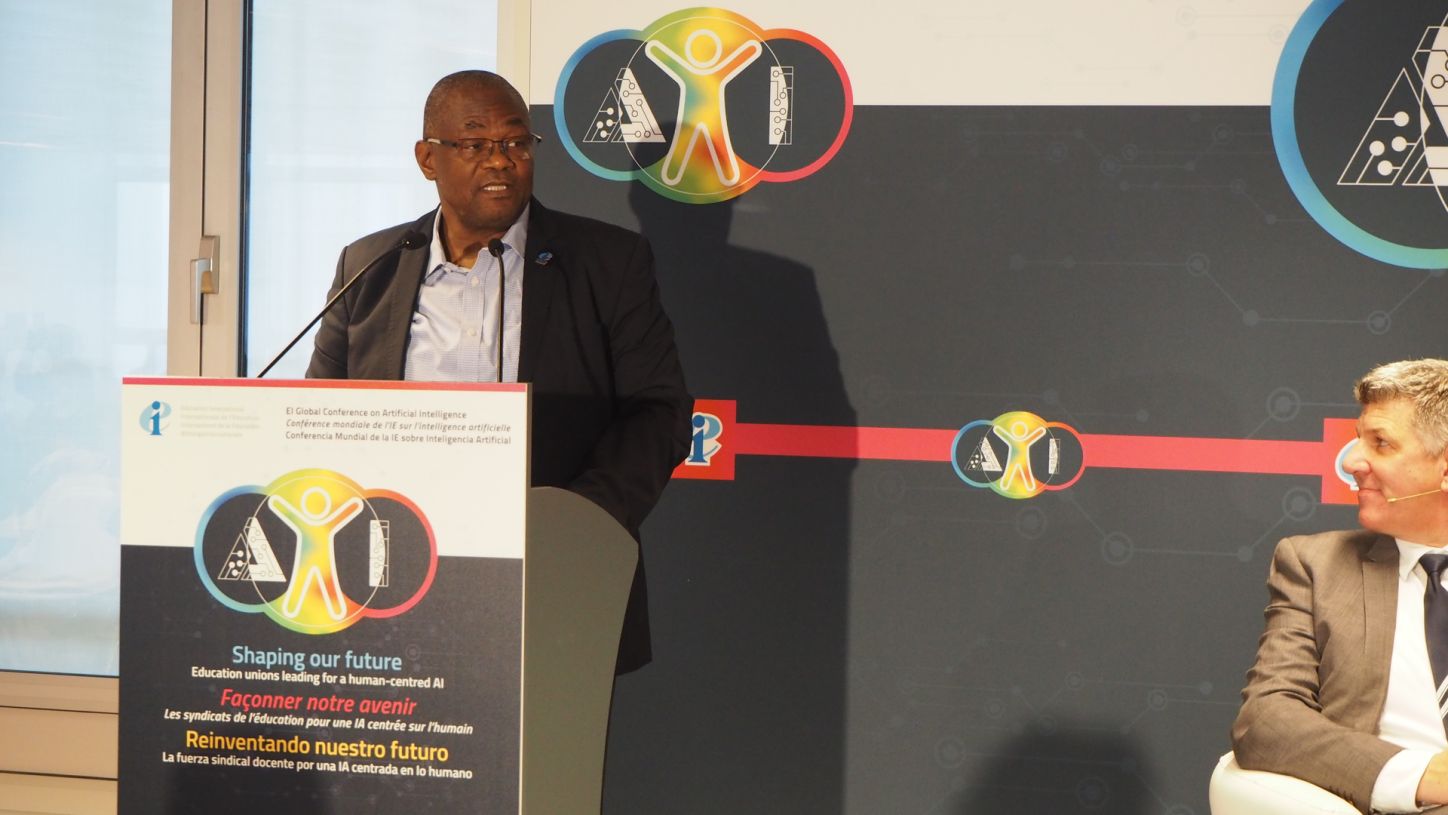

To confront these issues and set out a union-led vision for a human-centred future, Education International brought together more than 200 union leaders, educators and experts from every region for its first Global Conference on Artificial Intelligence, “Shaping our Future: Education Unions Leading for a Human-Centred AI”. The Conference was held in Brussels on 4–5 December and moderated by educator and thought leader Phil McRae of the Alberta Teachers' Association.

Over these two days, participants examined how artificial intelligence is reshaping education and work, and how unions can ensure that these systems strengthen, rather than undermine, public education, democracy and the teaching profession.

Technology may be the tool, but humanity is the author

Opening the conference, Belgian unions welcomed participants to Brussels in a joint address that crossed linguistic borders, demonstrating how unions in a multilingual country are working together to address data governance, infrastructure, and teacher autonomy in the face of new technologies.

EI’s President Mugwena Maluleke underlined that AI must never replace the human relationship at the heart of education. “Technology may be the tool, but humanity is the author. A chatbot can answer a question, but only a teacher’s voice can say: ‘I believe in you.’ Innovation must serve humanity, not diminish it. AI must amplify our voices, not replace them.”

Setting the scene: the real AI and its impacts

A shared keynote by Professor Wayne Holmes of the UCL Institute of Education and Professor Kyungmee Lee of Seoul National University, offered a critical overview of how AI is being deployed in education and what is at stake for students, teachers, and societies.

Holmes emphasised that many current claims about AI in education focus on efficiency and “personalisation” yet often ignore the hidden costs for teachers and learners. He showed how AI frequently shifts, rather than reduces, teachers’ workload: time is displaced into crafting prompts, checking and rewriting outputs, managing data and privacy, navigating ethical risks, and responding to students’ attempts to exploit AI’s weaknesses. At the same time, some education systems are experimenting with teacher-less or teacher-reduced models, raising major concerns about professional autonomy, accountability and quality.

Holmes also underlined the environmental costs of AI and the growing “AI divide” between those who have access to powerful systems and those who do not. Meaningful AI literacy, he argued, must include not only technological and practical dimensions but also the human dimension: understanding AI as a socio-technical system with implications for rights, democracy, and the Planet.

Professor Kyungmee Lee drew on research into South Korea’s AI Digital Textbook (AIDT) reforms to illustrate the politics of large-scale, top-down digitalisation. Promoted as a way to ‘personalise’ learning and modernise classrooms, the AIDT initiative met strong resistance from teachers, parents and civil society. Concerns ranged from excessive costs, data protection and commercialisation, to digital overuse, inequalities and a lack of meaningful consultation.

Lee’s work shows how AI in education reorganises classroom relationships: it reshapes students’ identities and peer interactions, reconfigures teachers’ authority and visibility, and creates new layers of hidden labour as educators struggle to make systems function in real schools. AI, she stressed, is not simply 'introduced' into education; it emerges from complex assemblages of ministries, companies, infrastructures, policy narratives and 'teacher data'. Teachers’ voices are often marginalised in these processes, and must be brought to the centre.

Union perspectives: nothing about us without us

Union leaders from different regions reflected on the realities in their contexts, from highly deregulated digital markets to settings where social dialogue and regulation play a stronger role. They shared examples of how unions are responding to AI-driven reforms, from bargaining over data protection and workload to contesting privatisation and defending public funding.

Across plenary and breakout sessions, several common themes emerged:

- AI must serve teachers, not control them: Participants welcomed tools that reduce admin work but warned against those that undermine professional judgment, increase surveillance or worsen workload. Teachers’ right to opt in, opt out, or refuse unethical systems was central.

- Critical AI literacy: Unions stressed that teaching with and about AI requires strong teacher training, grounded in human rights, democracy and sound pedagogy.

- Equity and data colonialism: AI is largely developed in powerful corporate and geopolitical centres, using data that can exclude or misrepresent communities. This fuels bias, discrimination and new forms of digital colonialism.

- Inclusion and disability: Assistive AI tools can support diverse learners, but must be evaluated through equity, rights and meaningful participation.

- Digital divides: Unequal infrastructure, commercial models and licensing regimes are creating new divides within and between countries. Unions called for public investment and resistance to dependency on private platforms.

Professor Punya Mishra, Director of Innovative Learning Futures at Arizona State University, closed the first day with a thought-provoking address. He urged participants to look beyond the hype and recognise AI for what it is: a probabilistic system that produces plausible text without true understanding. “AI can create content, but not context,” he noted.

Mishra cautioned that education is entering an unregulated global experiment in data colonialism, one that risks reinforcing echo chambers and diminishing spaces for authentic human dialogue. His core message was clear: educators must engage with AI realistically, not with blind trust in corporate promises.

From analysis to action: organising for the Future We Need

Day 2 of the Conference shifted the focus to action. The conversations moved from critique to strategy, as union leaders explored how to turn principles into power through collective bargaining and organising.

Breakout sessions tackled some of the most pressing union priorities in the age of AI. Participants explored how collective agreements can safeguard against deskilling, job loss, and unchecked surveillance, while setting clear limits on data use and automated decision-making. They discussed innovative ways unions are using digital and AI-enabled tools to engage members, always with respect for privacy, democracy, and workers’ rights. Finally, the sessions considered how global standards, including the ILO/UNESCO Recommendations on the Status of Teachers, must evolve to address new realities such as platform work, data governance, and algorithmic management.

In a session with international organisations including UNESCO, the OECD, UNICEF and the Global Partnership for Education, panelists warned of a widening policy vacuum, with AI advancing far faster than regulation or evidence.

They stressed the need for precision rather than hype, noting that many tools entering classrooms were designed for business, not for learning, and too often rely on training data drawn almost entirely from the Global North. This leaves many countries, languages and school realities effectively invisible in system design.

Across interventions, one message was clear: teachers must retain control over AI’s pedagogical use, and only a teacher-first approach can ensure that AI strengthens public education rather than undermining it.

Regional meetings allowed member organisations to formulate commitments for future work on AI in education. These ranged from national campaigns for robust legislation on data protection and AI in schools, to regional taskforces on AI, shared research agendas, and joint training programmes for union activists.

The day also highlighted the importance of a united front, developing common strategies and principles for negotiating AI regulations, ensuring the global education union movement speaks with one voice. Universities were identified as key allies in shaping ethical frameworks. Participants stressed the need for diversity at the decision-making table. Free, prior and informed consent must guide any AI development involving Indigenous communities, protecting intellectual and spiritual property and setting clear safeguards. Unions have a responsibility to inform their members, provide training, and develop the language needed to engage confidently in collective bargaining on AI.

We are not passengers in the future, we are its architects

EI’s General Secretary, David Edwards, outlined five strategic pillars that will guide EI’s work on AI:

- convening a global network to connect unions;

- sharing cutting-edge research;

- driving advocacy at international and national levels;

- building union capacity through training and organising; and

- providing thought leadership to keep teachers and human-centred education at the core of policy and practice.

These pillars will shape EI’s long-term strategy to ensure technology serves humanity and strengthens public education systems.

The conference closed with a powerful call to action from EI President Mugwena Maluleke, who reminded delegates that education must remain a profoundly human endeavour. “In an age of algorithms and automation, we are the light—the human wisdom that illuminates the path forward. AI may process data, but it cannot shine with insight, judgment, and humanity. That is our gift. That is our calling,” he said.

Maluleke urged unions to organise, advocate, and educate to ensure technology serves humanity, not the other way around. “Human First. Always. Teachers Lead. Technology Serves. Education Unites,” he concluded, calling on educators worldwide to defend professional autonomy, job security, and the dignity of teaching in the era of AI.

As the conference closed, one conviction was clear and shared: AI may be powerful, but organised educators, grounded in professional ethics, solidarity and a commitment to democracy, will determine the future of education.

You can access the Conference conclusions here