Climate education for sustainable futures: A cross-country study of India and Philippines

Sign up

Sign up for the Worlds of Education newsletter.

Sign up

Sign up for the Worlds of Education newsletter.

Thank you for subscribing

Something went wrong

Climate change is the ‘biggest modern threat that humans have ever faced’ (Eckstein et al. 2021). An apparently minor change in global temperatures, largely catapulted by human-industrial activities such as the acts of deforestation, burning fossil fuels and exploitation of natural resources, results in cataclysmic weather conditions, loss of biodiversity, food insecurity and even large-scale population displacement. While climate catastrophes are visible all over the globe, their impacts are exacerbated in the developing and impoverished nations (Taconet et. al., 2020). Hence, the role of a conscientious citizenry sensitized to the political debates of the times and committed to demand climate justice from their governments becomes critical.

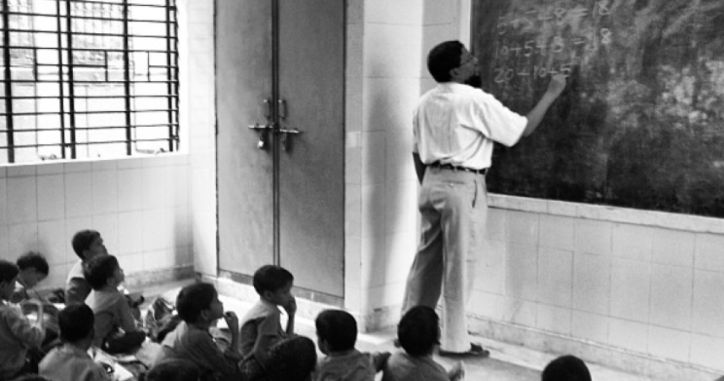

In this context, Climate Change Education (CCE) may pose as a medium to collectivize and mobilize both state and civil society in order to create a sustainable future for all (Education International, 2024). By democratizing knowledge, CCE can significantly contribute to disaster preparedness and address vulnerabilities, ensuring that communities are better prepared to make adaptive judgements with the help of a well-designed curriculum, suitable pedagogy, and learning tools (Pan et. al., 2023). Also, education has the potential to bring together national unions, educators, policymakers, and students to bridge the gap between climate science, justice, and policy.

As the countries of South Asia and Southeast Asia are particularly vulnerable to climate disasters owing to their distinctive socio-economic, political and geographic characteristics, a cross-country research project was undertaken, focusing on India and the Philippines. The study not only involved a critical assessment of climate education policies and national curriculum frameworks that incorporated CCE but also engaged in qualitative ethnographic research work in specific regions of both countries with the purpose of understanding realities on the ground and actual implementation in the schools.

Locating the discourse of climate change education in India

Given that India is one of the most vulnerable countries to the adverse impacts of climate change owing to its geographical diversity, high population density with rapid urbanization, and intense dependence on coal-based energy, its policies on climate change have been framed largely with the aim to reconcile economic growth and development with sustainable pathways (Dubash & Joseph, 2015; Nair, 2015). The relevance of environmental education was first acknowledged through the Kothari Commission (1964-66) that was later implemented in the National Policies of Education (1986, 1992), which emphasised building environmental awareness amongst children. The National Curriculum Framework (NCF 2005) included Environmental Studies (EVS) as a separate subject, at the primary level. The recent National Education Policy (NEP 2020) promotes a holistic, participatory, multidisciplinary, multilingual environmental learning rooted in local contexts, while also recognizing the transformatory role of teachers in fostering climate consciousness. The NCF 2023 further strengthens this vision by linking climate education to values, ethics, and sustainability, and importantly, acknowledges the role of traditional and Indigenous knowledge in environmental conservation.

And yet, it may be noted that despite mandatory teaching of the EVS from Grades I to XII by the Central Board of Secondary Education (CBSE), there is no explicit focus on climate change education (TESF, Background Paper, 2021: 18). Secondly, despite emphasis in policy and recent attempts to incorporate aspects of Indigenous knowledge in the National Curriculum Framework, there still remains a persistent gap and an epistemic hierarchy between the formal, “scientific” learning imparted in schools and the everyday experiences of the students, often disregarding their local, tacit and Indigenous perspectives, especially in the rural hinterlands. In Chunakhali village of Sundarbans in West Bengal, a young student from the local government school said, “schools only teach from books that have sections on climate change but nothing on Sundarbans [1]; books don’t teach us what is necessary for living and most importantly how to survive the calamities that hit us so often.” A similar concern has been raised by the principal of a local government school in Wadsa in the Gadchiroli tribal region of Maharashtra: “Understanding the science of climate change is important but how is climate change connected and is shaping lived realities? Indigenous culture is something students from this tribal locale are looking for. Without this dimension, climate education will remain abstract for them”.

Mainstreaming climate education in the Philippines

The other country under study, the Philippines, located in the Pacific Ring of Fire and the typhoon belt, faced with the additional pressures of increased development and tourism, has been immensely susceptible to climate catastrophes in recent years. Hence, the country has institutionalized climate change policies that emphasize both mitigation and adaptation. The Climate Change Act of 2009 (Republic Act 9729) seeks to align national efforts with UN’s Agenda 21 and has led to the creation of the National Climate Change Action Plan (NCCAP). Section 15 of the Act mandates the Department of Education (DepEd) to not only incorporate core climate change concepts and principles into primary and secondary education school curricula, integrating CCE into different science and social science subjects, but to also ensure inclusion of climate change education in the supporting texts, primers and instructional materials. Initiatives by DepEd also include the National Greening Programme, Youth for Environment in Schools Organization (YES-O), Handbooks for guiding teachers, and Gulayan Sa Paaralan (vegetable garden in school) that advocates for student involvement in climate action beyond the classroom. The K–12 Curriculum (Basic Education Curriculum) introduced in 2013 sought to integrate CCE across various subjects, with a specialized Disaster Risk Reduction and Management (DRRM) course included in the STEM strand at the senior high school level. In 2023, the MATATAG Curriculum was introduced to fill the lacunae in K–12, emphasizing skill-based learning. MATATAG notably seeks to incorporate Indigenous knowledge systems into science texts, particularly within topics related to agriculture, conservation, and traditional environmental practices.

However, considering the absence of a specific course/subject on climate change education to be taught from the initial levels of schooling and given that components of CCE are mostly dispersed across various disciplines of science and social science subjects, the burden of inculcating its relevance inevitably falls on teachers’ capacity to effectively incorporate them while teaching. While components of CCE are included in the science curricula, they feature less prominently in the humanities/social science subjects, which need to be revisited. Moreover, in a disaster-prone country like the Philippines, it is important that CCE is introduced in the foundational years, to foster an early awareness amongst children.

Vision-practice gap and recommendations

While both countries have sound national policies and curriculum frameworks that seek to incorporate relevant education and awareness on climate change and environmental conservation, there are distinct gaps between vision and practice on the ground. Intensive field engagements in Sundarbans (West Bengal), Gadchiroli (Maharashtra) and Delhi in India; and Metro Manila and Boracay Island in the Philippines reflected the disconnect in policy provisions related to CCE. The coordination mechanisms between the central, state governments and local governments regarding implementation of CCE in schools is weak and the challenges increase even more when political parties are feuding. Both countries are yet to have a specific CCE budget. Unless governments invest in CCE, developing mechanisms for building climate resilience through education will not progress. Additionally, both the countries are yet to adopt decolonial approaches and practices for CCE, which would ideally include a climate justice lens.

Teacher unions can play a critical role and, in both countries, teachers’ unions recognize the climate crisis as “a pressing labour rights issue”. The Alliance of Concerned Teachers (ACT) in the Philippines considers the fight for climate justice as an integral part of the union’s struggle for human rights and ecological sustainability.

First, for effective implementation of quality climate education in India and the Philippines, with the purpose of addressing this vision-practise divide, there is an urgent need to provide academic/professional support to the teachers who are faced with the actual burden of transmitting knowledge in classrooms. In this, education unions can play a significant role by creating an open access digital repository of reliable, relevant and innovative resources and pedagogical toolkits on climate change across disciplines in English as well as regional/local languages. Unions can also work with schools to organize workshops.

Secondly, there is a need to decentralize the discourse on climate education, to make it more inclusive and to integrate decolonial approaches and practices in school systems. Teachers’ unions can play a cardinal role in foregrounding Indigenous knowledge in the discourse on CCE so that such perspectives/narratives are brought to the regional, national, and global debates and negotiations.

And lastly, the longstanding issues in the education sector such as teacher shortages, regularization of teachers, improvements in working conditions and oversized classrooms must be addressed in conjunction with the implementation of CCE. Without meaningful reforms in the working conditions of educators, any policy that purports to champion quality climate education will only ring hollow. Teachers are at the core of CCE and education unions are well placed to advocate for CCE alongside their demands for greater funding for public education.

References

Eckstein, D., Kunzel, V., & Schafer, L. (2021). GLOBAL CLIMATE RISK INDEX 2021. In Germanwatch. https://www.germanwatch.org/sites/default/files/Global%20 Climate%20Risk%20Index%202021_2.pdf

EI. (2024a). Forging the education–climate justice connection. In Education International. https://www.ei-ie.org/en/item/28260:forging-the-education-climate-justice-connection

Facer, K., Lotz-Sisitka, H., Ogbuigwe, A., Vogel, C., & Barrineau, S. (2020). TESF Briefing Paper: Climate Change and Education. In Zenodo. https://doi. org/10.5281/zenodo.3796142

National Steering Committee for National Curriculum Frameworks. (2023). National Curriculum Framework for School Education 2023. https://dsel.education.gov.in/ sites/default/files/guidelines/ncf_2023.pdf

NCERT. (2005). NATIONAL CURRICULUM FRAMEWORK 2005. https://ncert.nic.in/pdf/nc-framework/nf 2005-english.pdf

Pan, W., Fan, R., Pan, W., Ma, X., Hu, C., Fu, P., & Su, J. (2023). The role of climate literacy in individual response to climate change: evidence from China. Journal of Cleaner Production, 405, 136874. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jclepro.2023.136874

Taconet, N., Méjean, A., & Guivarch, C. (2020). Influence of climate change impacts and mitigation costs on inequality between countries. Climatic Change, 160(1), 15–34. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10584-019-02637-w

The opinions expressed in this blog are those of the author and do not necessarily reflect any official policies or positions of Education International.