Not the exception, but essential: Teachers with disabilities in mainstream classrooms

Sign up

Sign up for the Worlds of Education newsletter.

Sign up

Sign up for the Worlds of Education newsletter.

Thank you for subscribing

Something went wrong

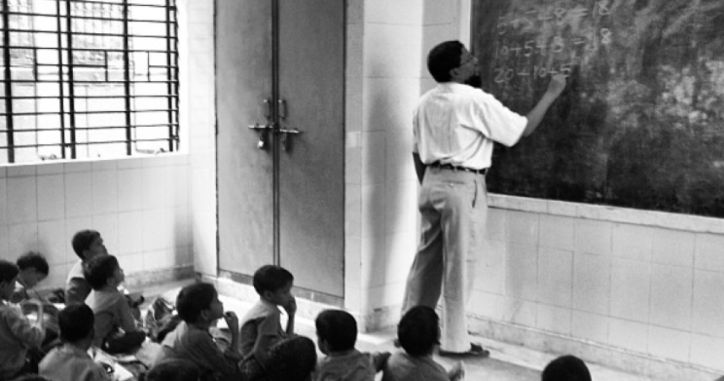

Where are the teachers with disabilities in our classrooms?

A question I often ask my audience is: “How many of you were taught by a teacher who identified as having a disability during your school years?” In a room of 50–60 people, usually only one or two hands go up.

This isn’t surprising. Teachers with disabilities are rarely seen in mainstream schools [1]—and there’s little reliable data about them across countries.

Globally, while there has been significant progress in including children with disabilities in mainstream education, these efforts rarely extend to teachers with disabilities. This is a missed opportunity. Existing research—though mostly from high-income countries—shows that teachers with disabilities, when employed in mainstream schools, can be powerful agents of change. They are often more likely to adapt lessons for diverse learner needs, serve as strong role models for students both with and without disabilities, and actively challenge societal biases.

Yet in low- and middle-income countries (LMICs), we know very little about their experiences.

To address this gap in knowledge, the Learning Generation Initiative (LGI) and the Cambridge Network for Disability and Education Research (CaNDER) – with support from the What Works Hub for Global Education - are launching a new research synthesis that summarizes the existing evidence on teachers with disabilities working in mainstream classrooms. Co-authored with Katie Godwin from LGI, this synthesis also provides insights from low- and middle- income country (LMIC) examples of how teachers with disabilities are included in education policy and planning.

The synthesis draws on data collected under the aegis of CaNDER, through interviews and participatory activities with teachers with disabilities across nine LMICs: India, Rwanda, Nepal, South Africa, Ethiopia, Kenya, Sri Lanka, Brazil, and Jordan. Teachers who participated self-identified as having a disability and had a range of functional limitations, largely in relation to walking, seeing and hearing.

The goal of the synthesis? To amplify teachers’ voices and propose clear, actionable recommendations rooted in both lived experiences and policy analysis. We also want to centre teachers with disabilities as unique experts and to value their perspectives in shaping more equitable educational practices.

What we heard from teachers

Disability is not a homogenous category and the intersections of gender, type of impairment, geographical region and other factors make it a highly complex experience; nonetheless, across all nine countries, teachers with disabilities shared strikingly similar stories. Many felt sidelined—given low-priority subjects, met with resistance from school leadership, and faced limited opportunities for career progression.

Yet their stories were also full of hope. Over time, and with growing familiarity, they built positive relationships with students and colleagues alike. What stood out most was their resilience and deep belief in the value of their work—especially in fostering inclusion and shifting perceptions of disability inside and outside the classroom.

Interestingly, many challenges reported by teachers in LMICs also exist in better-resourced systems, such as in England.

What’s happening at the policy level?

As part of this research, we looked across seven LMICs (India, Kenya, Ghana, Tanzania, Rwanda, Sierra Leone, South Africa) and found that national data on teachers with disabilities is rarely collected or used systematically. While half the countries reference representation of teachers with disabilities in policy, only Kenya sets specific recruitment targets. Four countries address infrastructure and access, and just three include pre-service education or professional development for teachers with disabilities.

Teachers’ recommendations for change

From their lived experiences, teachers identified the following priority areas for change:

1. Accessible school infrastructure

Most participants cited physical barriers: inaccessible buildings, gates, and even unsafe roads. In Ethiopia, teachers spoke of waterlogged roads during the rainy season. Teachers in India, Nepal, Rwanda, and Ethiopia highlighted a lack of accessible and clean toilets, rest areas, and basic sanitation facilities.

2. Accessible teaching resources and assistive devices

Many teachers lacked access to teaching materials in accessible formats. In Sri Lanka, the lack of Braille textbooks meant that teachers had no accessible materials to reference. As a result, they relied on students to help each other by calling out page numbers with the relevant content during lessons. Some teachers depended on friends or family to prepare teaching aids.

3. Improved use of EdTech

Teachers in Sri Lanka, India, Rwanda, and Ethiopia noted a serious lack of educational technology. Rakesh, a teacher in India, observed that while tech supports people with disabilities in other sectors, schools have yet to catch up.

4. Disability awareness among school leaders

Many teachers faced challenges due to lack of understanding from school leaders. Latifa, from Jordan, shared: “When I came to my school, the manager didn’t know how to deal with me, or what kind of work I could do.” Leadership often ignored or failed to address disability-related issues.

5. Professional networks for teachers with disabilities

Several teachers, especially in Ethiopia, expressed the need for peer networks. Serkalem, from Ethiopia, said: “Simply knowing there were other teachers like me would help.”

6. Clear policies and better implementation

While most countries have policies supporting disability rights, few explicitly address teachers with disabilities. Addisu, from Ethiopia, highlighted the policy-practice gap: “What is being talked about and what is actually being done is as different as heaven from earth.”

A call to action

Based on teacher narratives and policy insights, the research synthesis calls for actions in each of the following areas:

- Data: Include disability as a category in routine education data collection. This is a low-cost but crucial step for deployment, monitoring, and support.

- Research: Invest in robust evidence to fill current knowledge gaps—especially around the impact of teachers with disabilities on student learning and educational outcomes.

- Policy and practice: Develop inclusive education policies that support teachers with disabilities throughout their careers. Ensure access to teaching materials, mentorship, and professional development opportunities.

Teachers with disabilities are not exceptions to be accommodated, but vital voices that enrich the fabric of education—reminding us that true inclusion begins not at the margins, but at the heart of our classrooms.

A mainstream school refers to a regular educational institution that provides education to all students, including those with special needs. It is characterized by the inclusion of learners with special needs into general educational settings, allowing them to learn alongside their peers without disabilities. Mainstream schools differ from special schools, which cater specifically to students with particular educational requirements.

The opinions expressed in this blog are those of the author and do not necessarily reflect any official policies or positions of Education International.